May Songs:

Carvings after Pennsylvania German Folk Art

Sow a garden of flowers, let it go to seed, and the finches soon arrive to feed—which must be why the little birds that perch among the intricate floral designs of Pennsylvaanisch Deitsch folk art became known as distelfink, literally thistle-finch, the German name for goldfinch. But a bird is not merely a bird in this art, nor a flower merely a flower. If the garden in May with its fresh flowers and bright birds must soon decay in the way of all earthly things, it foretold the eternal May of heaven, where all bloom in harmony and human souls, taking flight like the birds of the air, at last feed in peace among the lilies.

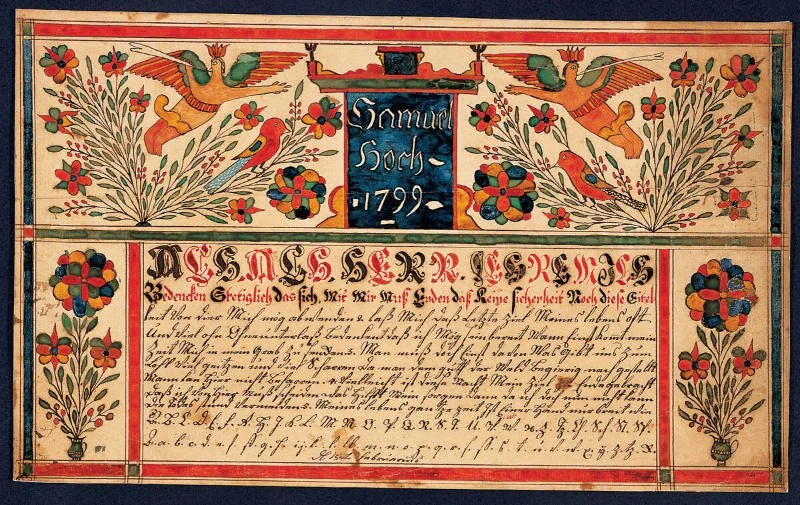

Vorschrift for Samuel Hoch, 1799, from the Oley Valley, Berks County, Pennsylvania.

Via The American Folk Art Museum.

Early German immigrants to southeastern Pennsylvania, especially the mystics at Ephrata Cloister and the pietistic Mennonites and Schwenkfelders, used such naturalistic imagery to illuminate hymnals and religious texts—hence the term fraktur, which referred originally to the “fractured” style of lettering but now includes the art that accompanies it. Over time, as a shared and increasingly secular culture grew in the region, the imagery merged with other traditions and grew more stylized and more purely decorative. Yet deep in its heart remains a vision, not merely of bountiful creation, but of redemption. As Francis Daniel Pastorius wrote in 1720,

In the wide world I find

Nothing but disturbance, war and strife.

In my little garden

Love, peace, rest, and unity—

My flowers never fight.

Severed by the Enlightenment from its Christian roots, this mystical imagery made its way into German Romanticism. In Johann Wolfgang von Goethe's poem “Mailied” (May Song), redemption comes from nature itself, and from earthly love:

How gloriously nature

gleams for me!

How the sun shines!

How the meadow laughs!Blossoms burst

from every bough,

and a thousand voices

from the shrubs,and joy and delight

from every breast.

O earth, O sun!

O happiness, O bliss!

I have taken my title from Goethe, but it is the religious art of early German Pennsylvania that inspires my work, and however I may experiment with its forms and its icons, I bear in mind its roots. After all, in my own garden, the finches arrive only after the flowers have gone to seed, not while they are still fresh and blooming! Like the sixteenth-century hymnist, “the maytime I mean gives eternal joy.”

Technical notes

I carve these designs in thin sheets of basswood using a chip-carving knife, then finish them with thin coats of shellac. The frames are carved with simpler patterns for contrast, painted milk paint, and finished with walnut oil and beeswax.